Part of the mission of the Seaford Review is to shine more of a spotlight on the people making, submitting, and working with poetry in 2024. Lyric doesn’t come out of nowhere, and too often the way we publish these days — particularly in smaller or ‘indie’ presses — cuts poetry off from the context which nourished and gave rise to it. We’d like to shift some of the focus back onto our poets, and the language-worlds in which they are working.

One of the ways we’ll do this is by offering our published poets the opportunity to do a Q&A, which will follow in the wake of the issue that features that poet’s work. As a way to kickstart this process, we thought we’d run an initial Q&A with our editors, starting with Jack. The idea is to help our readers get acquainted with the editorial team before submissions open in September, as well as with the rough format that the Q&A will take.

Jack is a poet and software engineer who grew up, and still lives in, London. He’s been writing poetry since he was a teenager, and was a past recipient of the Tower Poetry Prize (second place). For a taste of his writing, you can find Jack’s poem “Fountain” in a recent edition of Tin Can Poetry.

Luís Costa: Hi Jack, welcome.

Jack Westmore: Hi Luís!

Both laugh.

LC: To get things started, can you tell me a bit about your writing practice? Where and how do you write? Do you write by hand, in your phone, on a laptop…?

JW: On a good day, I feel as if I am constantly writing. I am always noticing things, taking notes in my phone about things I’ve seen or thoughts I’ve had, or turns of phrase I’ve heard… it’s a kind of madness. John Ashbery once said “the pathos and liveliness of ordinary human communication is poetry to me”, which is something I’ve always felt, and agreed with.1 You can find poetry wherever you look, if you’re looking the right way.

And sometimes I wish I could write it all down, because it seems so precious to me. Other times — the other day, for instance, when getting to the end of a lane in the swimming pool — I am suddenly shocked all over again, and out of the blue, that there is so much that I can’t remember: so much I’ll never get back.

LC: Would you say, then, that writing serves a kind of memorialising function for you?

JW: Definitely. I am a nostalgic person — although I say it slightly lightly, I am a Cancer, ha — and sometimes I think that I write because I’m sad and want to hold onto things. Plato said that originally, I think in The Republic: that writing is just a crutch for our memories. And remember, he was writing at a time when writing was a relatively new technology. Or at least, not available to everybody and kind of universal in the way it is nowadays. It’s hard for me to imagine a time when, if you couldn’t remember a thing, then it was probably lost for good…

But writing is also a way of making more of my experience. It’s not just about hanging onto it or recording it: it’s about giving meaning to, and understanding, it.

LC: About revisiting it.

JW: Right. And often when I am writing my journal — which I do by hand, actually, with a pencil, because it forces me to travel more slowly and take more care — I am by nature quite a slapdash person — it’s only then that I’ll start to understand why a particular thing stood out to me, why it spoke to me. By writing about it I might see why I wanted to write about it in the first place.

LC: Can you talk to me about one of your recent poems?

They discuss Jack’s poem “Fountain”.

JW: I can’t remember where this poem originally came from: it must have been from my notes or from my journal or from a memory I’d had. I have this bizarre memory of being in primary school, how there was this completely artificial divide between the older kids — who were 9 or 10 years old — and the younger kids. As one of the younger children, I remember the older kids were colloquially referred to as “the bigguns”, as if they were this kind of monster from the Brothers’ Grimm…

Both laugh.

I don’t know where that came from, but I do remember it being endorsed by the teachers, weirdly. They seemed to be completely foreign to us “younguns”, in another world. And anyway, I think that memory or that scenario was sort of in the back of my mind when I was making Fountain. Along with the other things one carries about, of course.

LC: So you could say that there’s an idea, in this poem, of the poet or author being an outsider to another group, wanting to be a part of that…

JW: Yes, exactly. It’s the kind of absurd scenario of somebody who wants to be in the ‘in group’ — when the stakes, in this case, couldn’t really be lower, because it’s about learning to use a urinal! — and feeling so pleased with oneself when one masters the techniques and “utterances” of that group.

LC: When the urinal isn’t simply a urinal.

JW: It’s symbolic of being something else: being a “big boy”.

LC: I sometimes think that a lot of poetry is written by outsiders. Or by people who feel as if they are outsiders, at least…

JW: I think that was kind of the experience which inspired this poem. But, you know, it’s also a kind of loss-of-innocence thing, right?

It’s humorous, of course, this scenario of being accepted by the father figure — or, presumably being accepted, as we don’t actually get the father’s response to the “success” of the boy figure — and also being accepted by the “big boys”, whoever or whatever they are. But you lose something of yourself spending so much time trying to be involved with others, and liked by them. That’s something I’ve had to learn.

LC: And there’s a slight sexual undertone to the “big boys”, too…

JW: Yep.

Both laugh.

LC: Tell me about a poem you wish you’d written.

JW: It’s not a poem, but I recently read Jessica Au’s short novel Cold Enough for Snow. I wish I could have written that book. It’s so beautiful and ethereal and poetic. And filled with longing, of course.

LC: Can you tell me what’s on your bedside table?

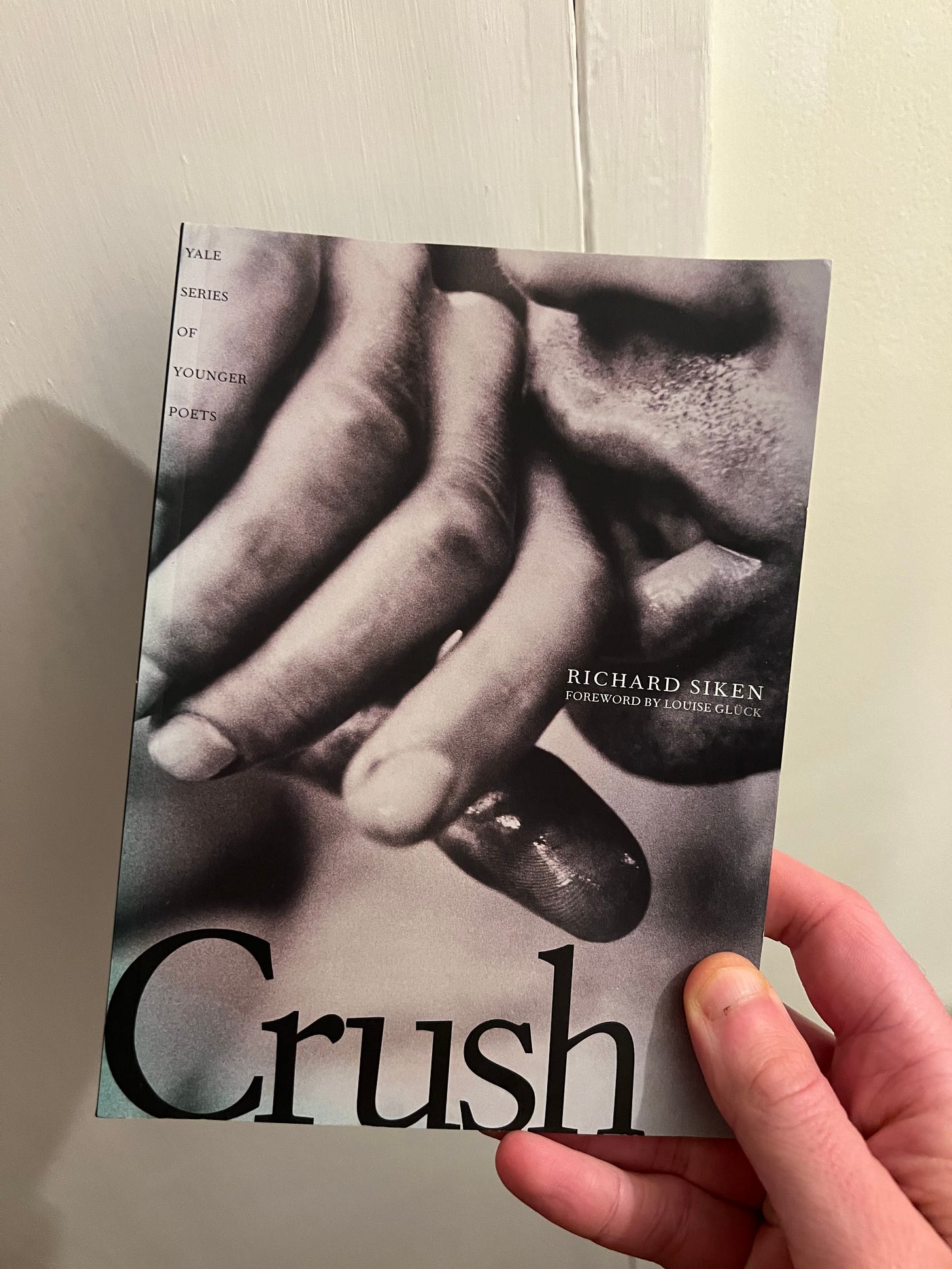

JW: Mostly books, of course, haha. At the moment I’ve been reading quite a few Yasunari Kawabata novels, so there’s a small stack of those. Eric Yip’s recent pamphlet, which I love and am absorbing at the moment. A copy of Richard Siken’s Crush, another favourite, James Baldwin’s Go Tell It On The Mountain, which I borrowed from my father’s library lately. A scifi novel I’ve been meaning to read for ages. My house keys and earphones…

LC: That’s a diverse selection!

JW: It’s pretty aspirational ha. There are some other things there too, but I could go on…

LC: Lastly, what are your aspirations for the Seaford Review? What hopes do you have for it?

JW: I think there’s an amazing undercurrent or underscene of people writing and making and involved with poetry in all kinds of ways, at the moment. My father pointed this out to me recently, when I was talking with him: how it struck him as almost strange that there was so much poetry being made at the moment. It seems to be there wherever you look. There are so many good independent presses and online literary magazines and spoken word or open mic nights.

But I don’t think it’s that strange. In fact, it seems pretty obvious to me: we live in extraordinary times, where the world seems to be continually disappearing and remaking itself before our very eyes. It’s no wonder for me, that in the midst of that, people would turn to poetry as a way to try and understand and communicate something of their inner experience. Even just a small part. Above all else, I hope that, with our work, we can provide a forum — a space — to give room to some of that expression.

Submissions for the first edition of the Seaford Review will open in September. Stay up-to-date by following us on Instagram and X/Twitter.

From Ashbery’s interview in issue 90 of the Paris Review (winter 1983).